Gerrymandering and geographic polarization have reduced electoral competition

Our newest working paper studies the changes in geography and gerrymandering across the 2010 and 2020 cycles. We find that competition has greatly decreased across time and that this is largely driven by changes in geography, but that gerrymandering augments this decrease. Changes in seats are relatively smaller, with a 4 seat decrease in the Republican bias attributable to geography and a 2 seat decrease attributable to gerrymandering.

Our new working paper studies the changes in political geography and gerrymandering since 2010. We introduce a new set of redistricting simulations for the 2010 cycle, which supplement the existing 2020 simulations for all 50 states. Comparing these two sets of simulations, we can isolate the changes in political geography. We can also isolate the effects of gerrymandering by comparing the enacted plans to the simulations in each year.

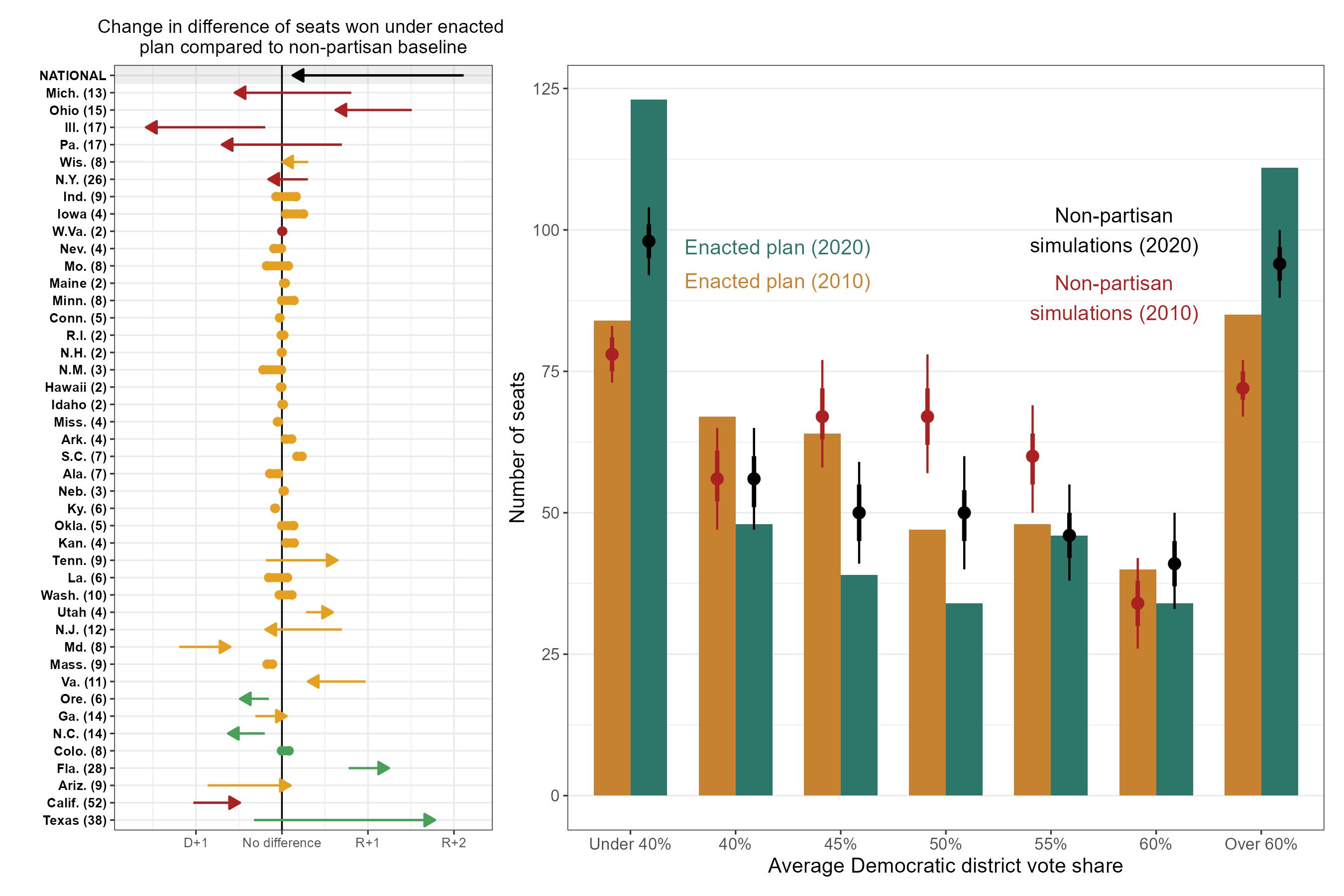

The left panel of the above figure (Figure 2 in the paper) shows how the gerrymandering has changed state-by-state and nationally between 2010 and 2020. While the total amount of gerrymandering at the state-level increased, the net effect of gerrymandering on the partisan balance of the U.S. House decreased.

However, the right panel shows the real loser in all of this: competitive districts. Changes in geography alone would have reduced the number of competitive districts by about 17 districts. Gerrymandering adds to this decrease, reducing the number of competitive districts by another 16 districts. Interestingly, this is only a slight decrease in the number of competitive districts lost due to gerrymandering, as compared to the 2010 cycle.

If you’re interested in reading the paper, check it out here. The full abstract is below.

Changes in political geography and electoral district boundaries shape representation in the United States Congress. To disentangle the effects of geography and gerrymandering, we generate a large ensemble of alternative districting plans that follow each state’s legal criteria. Comparing enacted plans to these simulations reveals partisan bias, while changes in the simulated plans er time identify shifts in political geography. Our analysis shows that geographic polarization has intensified between 2010 and 2020: Republicans improved eir standing in rural and rural-suburban areas, while Democrats further gained in urban districts. These shifts offset nationally, reducing the Republican geographic advantage from 14 to 10 seats. Additionally, pro-Democratic gerrymandering in 2020 counteracted earlier Republican efforts, reducing the P redistricting advantage by two seats. In total, the pro-Republican bias declined from 16 to 10 seats. Crucially, shifts in political geography and gerrymandering reduced the number of highly competitive districts by over 25%, with geographic polarization driving most of the decline.